EVs Are Just Going to Win

One of the most important and positive trends in recent years is the remarkable progress in battery technology. Significant increases in energy density and substantial declines in manufacturing costs have made batteries competitive with combustion engines across a variety of applications, most notably in transportation.

At the beginning of this year, the prevailing narrative was that electric vehicle (EV) sales were slowing down. Critics argued that EVs were a passing fad, that interest was waning, and that inherent problems would prevent them from ever displacing internal combustion engine (ICE) cars without subsidies. Essentially, the claim was that the EV revolution was over or at least indefinitely stalled.

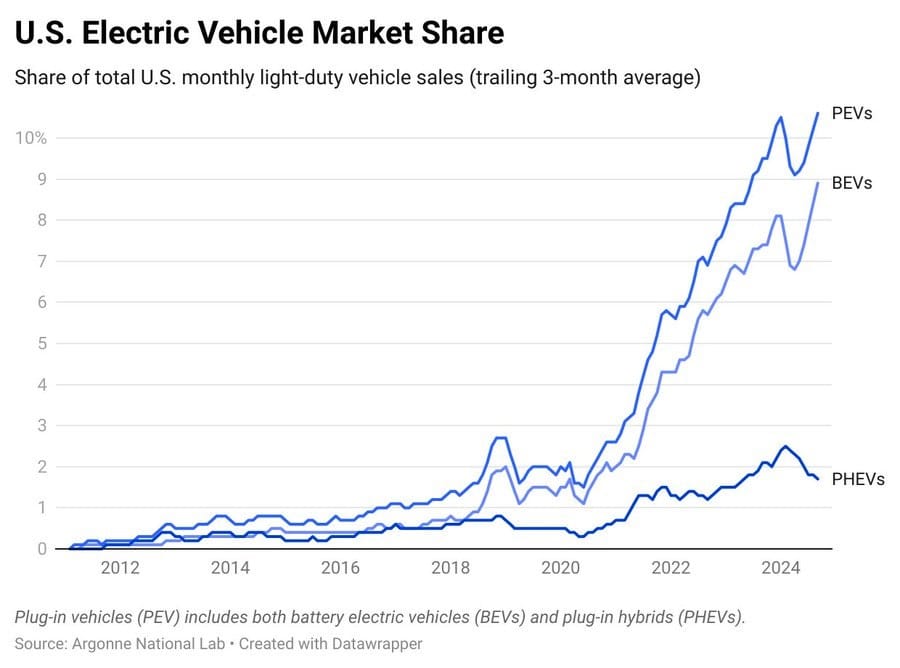

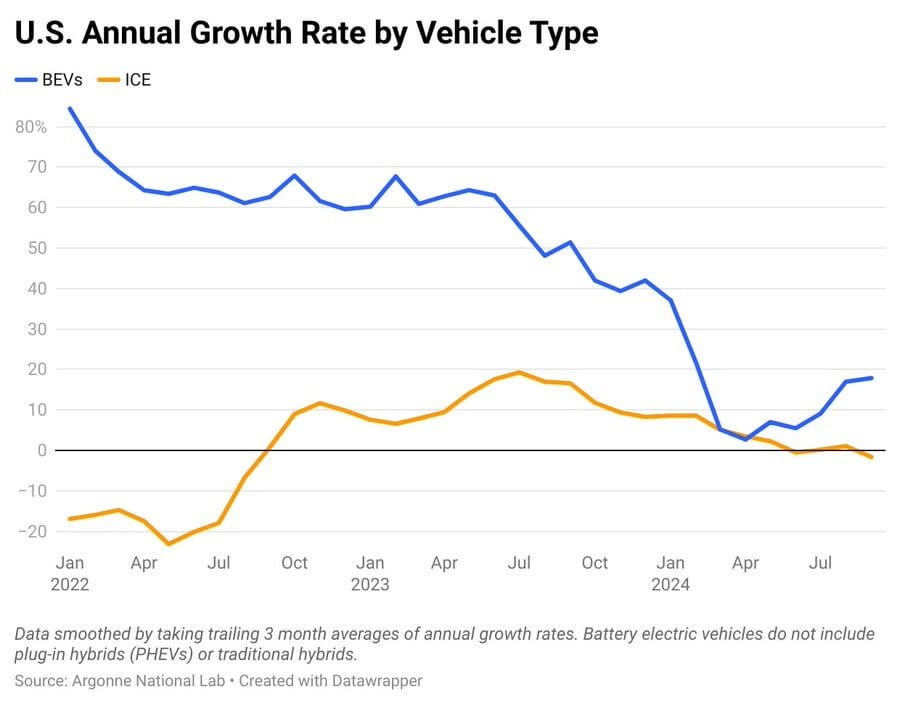

That narrative has now essentially collapsed. EV sales in the U.S. reaccelerated after just a couple of months, and their market share has hit a new record high (Source: Michael Thomas).

Furthermore, EVs continue to outsell combustion cars (Source: Michael Thomas).

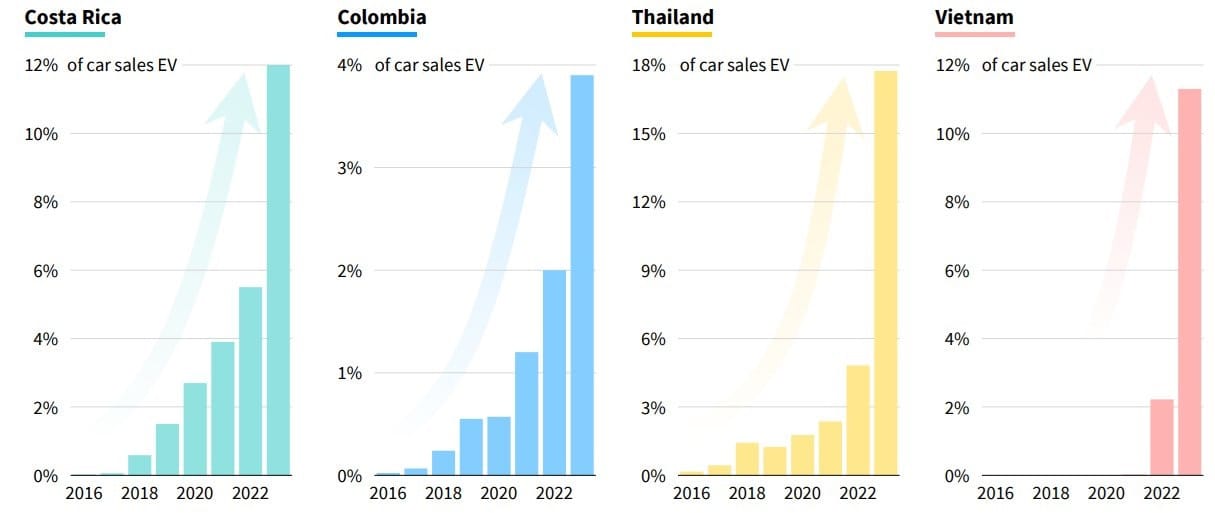

There is also no sign of a slowdown at the global level (Source: BNEF via Colin Mckerracher). Several developing countries are experiencing spectacular growth in EV sales (Source: RMI).

While EVs are still gaining ground, they have not yet dominated the market; only 4% of the global passenger car fleet, 23% of the bus fleet, and less than 1% of delivery trucks are electrified. However, the writing appears to be on the wall. The phenomenon of a superior technology displacing an older, inferior one is common, and the current EV transition aligns with this pattern. When a new technology surpasses a 5% adoption rate, it rarely turns out to be inferior to its predecessor; with EVs, that threshold has now been reached in dozens of countries.

In fact, trend-based forecasting is not necessary to understand why EVs are poised to prevail. There are several fundamental factors that make EVs superior to combustion vehicles. Over time, these inherent advantages will become increasingly evident in the market.

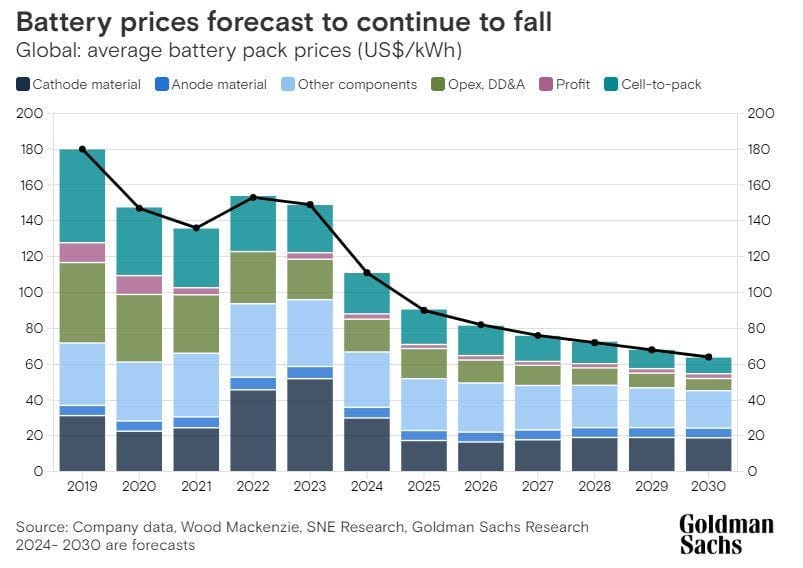

Price is the first of these advantages. Currently, EVs often require government subsidies to be price-competitive with combustion cars. However, battery costs are decreasing as manufacturing technologies improve. As batteries become cheaper, the subsidies needed to encourage people to switch to EVs diminish. According to a briefing from Goldman Sachs Research:

Technological advances designed to increase battery energy density, combined with a drop in green metal prices, are expected to push battery prices lower than previously expected... Goldman Sachs researchers further predict that average battery prices could fall as far as $80/kWh by 2026, equating to a drop of almost 50% from 2023 levels. It is at this point that the investment giant expects battery electric vehicles could potentially achieve cost parity with ICE vehicles in the United States on an unsubsidized basis.

Once batteries cross that tipping point, the EV revolution will gain its own momentum. It will simply become cheaper to buy an EV than a combustion car. Consumers will naturally gravitate toward the more affordable option, especially when it offers additional advantages—and in this case, it does.

The second advantage of EVs is convenience. Most EV owners will almost never have to fill their cars at a station because they can charge them at home overnight in their own garages or driveways. For example, the BYD Atto 3 has a range of 260 miles. Suppose one only charges the Atto 3 halfway every night to preserve battery life (similar to how many manage their phone batteries); that's 130 miles. To be conservative, let's say one limits driving to 100 miles per day.

Very few Americans drive more than 100 miles per day—the number is less than 1%. In fact, the average miles driven per day is around 40. This means that, as an EV owner, on most days when driving less than 100 miles, there is no need to visit a charging station at all, just as one doesn't visit charging stations for a phone.

Many Americans may not yet fully appreciate this fundamental aspect of EVs. Having spent their entire adult lives periodically visiting gas stations to fill up, they might naturally imagine doing something similar with an EV—visiting a charging station whenever the battery gets low. However, that's not how EVs work; they are more akin to a phone than a traditional car—you plug them in at home, so you almost never have to charge them when you're out and about.

Of course, this setup doesn't work for everyone, as not everyone has a place to charge their car at home. For those who use street parking instead of a driveway or garage, owning an EV becomes more challenging. However, fewer than 10% of Americans park on the street when at home. For residents of apartment complexes, it is expected that these complexes will eventually install EV chargers in most or all parking spaces, especially as EV adoption increases.

This means that directly comparing the time it takes to charge an EV versus filling up a combustion car's gas tank is misleading. With a combustion car, one might visit the gas station about once a week, spending approximately eight minutes each time. With an EV, it might take 30-40 minutes at a station to charge fully, but visits to charging stations are rare. EV owners typically only need to charge at a station during road trips or on those infrequent days when driving more than 100 miles. Therefore, the proper comparison of refueling times is "eight minutes every week" versus "30-40 minutes on very rare occasions." The latter is significantly more convenient.

EVs' third significant advantage is that they require much less maintenance compared to combustion cars. A combustion car has a complex engine with many moving parts, all of which can fail. An EV is much simpler, drawing energy directly from the battery with far fewer mechanical components. A simpler design means fewer parts that can break down, which is why EV maintenance costs are approximately 50% lower than those of combustion cars.

The fourth advantage is faster acceleration. Acceleration is a key aspect of driving enjoyment, and EVs outperform combustion cars significantly in this area. A battery-powered electric motor can begin accelerating the car with maximum force almost instantaneously upon pressing the pedal. In contrast, a combustion car must burn gasoline and engage multiple gears before acceleration begins. Consequently, EVs will always be able to go from 0 to 60 mph faster than combustion cars.

EVs' fifth advantage is quiet operation. Combustion cars generate significant noise due to controlled explosions and numerous moving parts. In contrast, EVs are incredibly quiet because they operate by simply pushing electrons through wires. This substantial reduction in noise is beneficial for drivers who wish to enjoy music or podcasts while driving. It also contributes to a quieter environment for neighborhoods—the fewer roaring combustion cars on the streets, the more peace and quiet for everyone.

This represents a significant suite of technological advantages for EVs. What advantages do ICE cars still possess? The range advantage has largely disappeared, with many EVs now offering ranges exceeding 300 miles. The slight remaining cost advantage of combustion cars is poised to become a cost disadvantage within a few years, even without subsidies. Their quicker refueling time seldom comes into play, as EV owners rarely need to charge away from home.

Apart from the familiarity born of long use, there are few significant, enduring advantages for combustion cars over EVs. As EVs become more popular, combustion cars will become increasingly inconvenient due to a "doom loop." This phenomenon occurs because the more gas stations there are, the more convenient it is to drive, and the more people drive, the more profitable it is to run a gas station. This mutual reinforcement explains the abundance of cars and gas stations.

By reducing internal combustion traffic, EVs will make gas stations less profitable. Gas stations have fixed costs that require serving large volumes of customers; with fewer customers, it becomes harder to cover these costs, leading some stations to close or convert (possibly to EV charging stations). As the number of gasoline-powered cars decreases by double-digit percentages, numerous closures or conversions are likely.

When gas stations disappear, driving a combustion car as the primary mode of transport becomes more difficult due to fewer and more distant refueling options. This creates range anxiety on long trips and forces drivers to travel farther for fuel, providing an incentive to switch to an electric vehicle.

This network effect is another subtle advantage of EVs over combustion cars. Combustion cars rely on a nationwide network of gas stations to be usable, whereas EVs primarily charge at home and depend less on a network of charging stations.

In conclusion, EVs are a superior technology compared to combustion cars. They will soon be cheaper, more convenient, easier to maintain, more powerful, and far quieter. They are poised to replace combustion vehicles; it's just a matter of time.

American industry needs to recognize this reality. Currently, Chinese auto companies have been far more aggressive than their established rivals in transitioning to EV technology. Bloomberg's Gabrielle Coppola and Danny Lee provide an excellent, sobering feature on the rise of China's electric auto champion BYD:

Now executives from Detroit to Tokyo have to figure out how to compete with BYD, and they know tariffs alone won’t cut it. For years, they couldn’t or wouldn’t make the case for cannibalizing profitable business with an expensive, technologically novel experiment such as the electric vehicle, and now it’s unclear if they’ll ever catch up. The Alliance for American Manufacturing (AAM), a lobbying group representing American companies and labor groups, has called China’s EV offensive “an extinction-level event” for the American auto industry. They realize BYD has built EVs that many Americans, starved for an affordable option, would probably be happy to buy.

Tesla was America's answer to BYD; indeed, it did more than BYD to pioneer many key technologies in the EV revolution and to drive down costs in the 2010s. It remains (just barely) the world's top electric car seller. However, in the last year or two, Tesla has stumbled, losing some EV market share to traditional auto companies in the U.S. domestic market and facing an increasingly uphill battle against domestic champions in China. Hopefully, Tesla will recover its footing, but even if so, the U.S. needs more than one EV champion.

Despite the U.S. lagging, the EV revolution is a great development for the world. In addition to directly benefiting consumers by providing better cars, the rise of EVs will help mitigate climate change. It is definitely a reason for optimism in these troubled times.